We Are Still Living in the Post-War Era

WWII continues to define modern politics – this needs to change

If the coverage around the not-entirely-shocking-but-still-surprising German election results earlier this week tells us anything, it is that the shadow of Nazi Germany still looms large over Western politics. Not because a quasi-fascist party is one bad electoral term away from European leadership: Orban has been in power in Hungary for nearly 15 years, Giorgia Meloni is over halfway through her first prime ministerial term in Italy, and France’s RN were a hairsbreadth from victory in last year’s French election – Europe’s fascist problem has never quite gone away. No, the shadow of Nazi Germany is felt so suddenly because of the discourse surrounding the AfD’s near-victory: Aren’t the Germans still ashamed? I thought Hitler had scared them off for good?

These reactions have been clogging up my social media feeds (yes, even my Substack) since the election, and they betray a worldview that has shaped Western politics for 70 years. This worldview defines geopolitics, underpins national myths, and has been used to justify conquest, invasions, autocracy, and warfare throughout the 20th and 21st centuries: the Nazis are the baddies. We are the goodies.

It sounds childish, because it is. But this worldview that is so simplistic, so ahistorical, so without nuance, has been so consistently drawn on by the former Allies since WWII ended that, 200 years from now, I have no doubt that historians will look back on our time and conclude that we are still living in the post-war era. An era whose discourse, politics, media, and culture continues to be defined by the events of a conflict that ended before many, many of us were born. Far from protecting liberal democracy, it's helping to unravel it. But if we're still living in the post-war era, how do we finally leave it behind?

Will the real Nazis please stand up?

If you want to see how well the blitz spirit lives on in the UK, one need only visit your nearest far-right nationalist rally. From the perennial remembrance poppies, to the spitfire-adorned banners, and the Churchill-esque ‘V for victory’ hand signs favoured by Britain First leaders, there is a self-assuredness in the way in which WWII imagery has come to underpin a very particular view of British history. It doesn’t matter that the views of groups like Patriotic Alternative, Britain First, or the Reclaim Party bear a certain resemblance to those of Nazi Germany: one of aggressive nativism, cultural superiority, xenophobia, and overt racism. No, the less this symbolism relates to actual ideology the better. Rather, this imagery harks back to a time of British supremacy, superiority, and moral infallibility. A time of Rule Britannia. A time, some may say the only time, when we were definitely, definitely, in the right, fighting a war against a genocidal, meth-addled despot hell-bent on world domination, the plucky underdogs who overcame the closest thing humanity has seen to pure, unambiguous evil. It’s a comforting fantasy – one that allows the inheritors of fascist ideology to wrap themselves in the symbols of its defeat.

Britain First leaders, doing their best Churchill impression (image via)

If the brave men and women of Britain’s resurgent far-right are indeed still at war, then who are the Nazis? It could be LGBQT+ activists. Laurence Fox did, of course, liken the Progress Pride flag to the Swastika during a 2023 libel trial. It could also be the EU, the founders of which were, if you were to believe former UKIP MEP Gerard Batten, the Nazi Party. In 2015 you might be forgiven for thinking that those seeking greater rights and equality for women were the Nazis, with the term ‘Feminazi’ peaking in popularity . The SNP have, at points, been the Nazis. Those advocating for the COVID lockdowns were also the Nazis. Black Lives Matter are the Nazis. Woke culture are the Nazis. At this stage, I can’t completely rule out the possibility that I, in writing this piece, may in fact be the Nazis.

It is all completely meaningless. A fantasy baddie in a fantasy war. The fact is that anyone who disagrees with the perspectives of this overly-nostalgic, puerile facet of British politics is at risk of being branded a Nazi. And not because they (we?) bear too much resemblance to Hitler, rather, it is those on the right’s sycophantic need to emulate the bulldoggish image of Churchill. They are in the right. They are in the right just as they were in 1939. The paragons of all things British. The goodies.

This spin on WWII may be uniquely British, but the sentiments are not. If Vladmir Putin doesn’t quite want to be Churchill, then he certainly wants to be Stalin. He justified his invasion of Ukraine by claiming that the country was in the grip of a Nazi dictator. To this day, a concerted disinformation campaign is being run from Russia to emphasise the supposed Nazi sympathies of Zelenskyy, including claims that he spent $15 million to buy Hitler’s parade car in 2024.

Trump seems characteristically confused about who he wants to be. Definitely not FDR. Possibly Truman? Or maybe Churchill. Or it might in fact be Hitler? No, Kamala was Hitler. Zelenskyy isn’t quite Hitler, but he is a “dictator without elections” – possibly a Nazi. Trump is “the opposite of a Nazi”, but he might also want to be a Nazi, if his rhetoric, architectural policies (shameless self-plug there), and dictatorial moves are to be believed. Trump might also want to be Stalin, with aims to extract the mineral resources of Ukraine with all of the grace and precision of the USSR at Chernobyl. We’ll have to return to this one in a year or two.

Viktor Orban has decided that NATO are the Nazis, for dragging Hungary into war over Ukraine – never mind that one of his closest advisors stepped down in 2022 after describing one of his speeches as “pure Nazi text”. Geert Wilders, in defiance to the idea that he is “some kind of Nazi”, instead thinks Muslims are the Nazis – a point with which Netanyahu agrees.

Across the UK, Europe, and the US, ‘Nazi’ has become a cultural touchstone, a meme of the far-right, a way of underscoring how they are, as ever, in the right, just as they were in the 1940s. But how has this come to pass – and why do so many of us still fall for it?

The war will be televised (forever more, apparently)

As I was conducting work for my PhD, I ran an analysis of how often different time periods were the focus of historical on-screen media (films, TV series, documentaries), in the 21st century. I had expected (and, for the sake of my argument, hoped) that content on the Greek and Roman periods would rank highly, given their popularity in the 20th century. I had not accounted for the WWII effect.

This was a comprehensive analysis. I looked at every historical documentary, TV series, or film produced by, or in conjunction with, a British studio, between 2000 and 2020, numbering nearly 1200 titles. Of these, 111 were focused on either WWII, the Nazi Party, or the Holocaust, representing nearly 10% of all the media that I looked at. Across the whole sweep of human existence, 10% of all historical media produced in the UK focussed on just 12 years. For context, that is three times as many as focussed on Ancient Rome (leading to some hefty rewrites for me), more than double the coverage of the entire medieval period, six times as much as the British Empire, and four times as much as the whole non-European world before colonialism. Meanwhile, only one documentary explored Jewish history without an explicit focus on the Holocaust.

I also ran an analysis to determine which themes were the most popular with audiences, using the number of IMDb ratings as a proxy for viewership (one has generally watched a film that they leave an online review for). After controlling for outliers, WWII emerged as the fourth most popular time period, out of the 48 that I analysed, behind content concerning the British monarchy, the Cold War, and the medieval period, with an average of nearly 23,000 IMDb rating per show or film (the single documentary on non-Holocaust Jewish history, by the way, received 286 ratings).

Please get in touch if you are interested in seeing my full results here – my thesis is currently not available online but I am happy to share the data from this.

So there is a hell of a lot of content on WWII, and people tend to watch it. But why? One of the foremost writers on nationalism, Eric Hobsbawm, has argued that the idea of the modern nation is inseparable from that of warfare. With no more kings, fiefs, and aristocrats to raise an army when faced with foreign aggression, it fell to the state to raise up and mobilise large numbers of citizens at times of war. This required a national ‘feeling’, the idea that these citizens held an obligation to fight a common enemy for the good of the nation. WWII was not the first war in which this national feeling played a central role, but it was the biggest. An unprecedented number of soldiers were raised, leaving huge gaps on the home front, which were filled by women who had traditionally not participated in heavy industry. Food scarcity in the face of a German blockade, combined with the damage inflicted by the Luftwaffe led to looting, which needed to be curtailed. The threat of infiltration, sabotage, and spies was ever-present. In short, Britain was ready to implode – and the national myths that we are still living with were forged in the effort to stop that from happening.

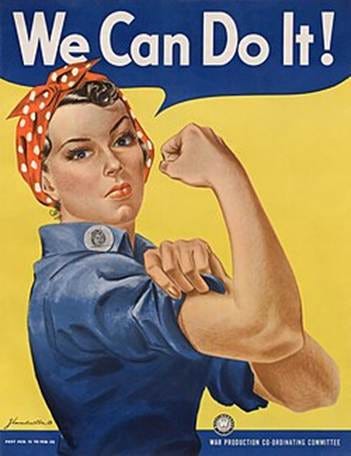

It helped that Hitler was a bona fide boogeyman. What did the Nazis have in common with every single TV bad guy? Black leather uniforms, and a sincere desire to take over the world. This was, broadly speaking, an easy sell to the British public. Anyone who has taken GCSE history will remember Britain’s WWII propaganda posters, emphasising the unity of the British underdogs against the ‘Axis of evil’. There was the nightmare-inducing Churchill-bulldog (see cover image, at your own peril); the faux-feminist ‘we can do it’; or the shadowy German soldier, peeking behind the walls-with-ears. All of the social, cultural, and historical complexities of WWII distilled into a simple, binary message: we are the goodies, they are the baddies.

‘We can do it’ propaganda’

This was, I hasten to add, entirely necessary. But the unintended consequences of this mainline hit of undiluted, nausea-inducing jingoism have lingered on ever since. What was once a necessary fiction became indisputable fact. This was not just a military victory, but a moral, even a spiritual one. We are right, we have always been right, and we will always be right. The wartime posters were telling the truth. Alongside this, the struggle and hardship of the war became central fixtures of our national myth. The spitfires. The Battle of Britain. D-Day. The Blitz spirit. These were not things that we endured in the face of enemy hostility. No, these are the things that we did to win. To win a war against a genocidal regime who would have readily overtaken these fair isles and put us all to death. Or worse, we would all be speaking German today were it not for…

Our victory, in short, became our national story, our national identity, reinforced through repeated documentaries, TV series, films, museum exhibits, political speeches, references to the ‘Blitz Spirit’ in the face of even the slightest collective hardship. We are British, because we are not Nazis. We beat the Nazis because we are British. And anyone or anything that stands in opposition to a very narrowly-defined image of our Britishness must, therefore, be a Nazi. In protecting this myth, we leave ourselves dangerously ill-equipped to recognise what fascism actually looks like today.

We were all the Nazis all along

Even in the 1940s, the idea that Nazism was, Mussolini’s earnest attempts at dictatorship aside, the only valid form of fascism, and thus that fascism was some faulty variant within the German (and Italian) psyche was pure fiction. Wartime propaganda. Hitler’s influences and inspirations were drawn from far and wide across occasionally fringe, but largely mainstream European thought over the preceding 100 years or so.

The idea that some groups, and specifically Semitic peoples, were incompatible with European society by virtue of their inherent impurity originated with the Spanish Inquisition. The limpieza de sangre (literally ‘purity of blood’) laws that were passed in the 15th century legitimised the expulsion or execution of Jewish or Muslim Spaniards. These laws are widely acknowledged as the basis for scientific racism as it emerged 300 years later through the work of British eugenicists such as Francis Galton, French theorists like Lapouge, and yes, Germans like Ernst Haeckel. In the interwar period, there were programmes of forced sterilisation for racial minorities and other groups in Belgium, Sweden, the US., Canada, and Brazil, building on concerted efforts to impose such legislation in the UK and France. Churchill himself was horrifically racist, harboured sympathy with eugenics, and was arguably complicit in genocide-by-neglect during the Bengal Famine.

The views on racial superiority that defined the Nazi agenda were always a pan-European and transatlantic project. I would argue that the wrong person, at the wrong time, in the wrong place, under the wrong conditions, could have easily emerged as the UK’s Hitler, France’s Hitler, Denmark’s Hitler (the USA’s Hitler may or may not already be in office, but, as noted above, we will return to this once he has decided). But at least we defeated the Nazis, and presumably their intolerant views. It is the thing that we are most proud of, of course. But what about racial segregation in the US well into the ‘60s? The colour bar in the British workplaces, only repealed in 1968? South African apartheid? The Contras in Nicaragua? The Pinochet regime? The Gaza genocide? All supported by contemporary British governments, or in some way beneficial to our foreign policy aims.

Think now of the ways in which migrants are spoken of by our own, supposedly ‘centre-right’ politicians. Hordes. Invaders. Swarms. Insects. Does this bear a certain resemblance to anyone? But we can’t be the Nazis! We defeated the Nazis. We are British because we defeated the Nazis. We defeated the Nazis because we are British.

The simple fact is that our mainstream politics of the post-war, interwar, and the Victorian periods have always had a significant overlap with the same ideas of cultural, social, and sometimes biological superiority that underpinned the Nazi movement. We just have different frames of reference. Hitler had the Anschluss, we have Brexit. Hitler had the Rhineland, we have the Falklands. Hitler had the Treaty of Versailles, we, well, have Hitler.

It is high time we stop glorifying our great moral victory, at the cost of ignoring the creeping immorality around us. Fascism can emerge anywhere, anytime, and is becoming more mainstream in front of our very eyes, even as we pat ourselves on the back for defeating it for good 80 years ago. We can take pride in this victory only if we ensure that it is a victory. A victory against the impulse to divide, exclude, and dehumanise, and not just a victory of British intolerance over German intolerance. If we keep looking for Nazis in brownshirts, we’ll probably miss the ones in pinstripes, Union Jack flags, or god-awful Lonsdale trainers.